|

|

|

|

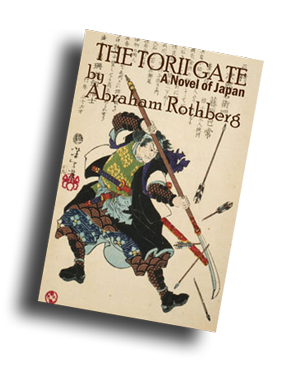

New by Abraham Rothberg: The Torii Gate: A Novel Of Japan $13.95 Printed: 253 pages, 6.0 x 9.0 in.,

The house came as a shock each time, jarring, as if he had missed the last step in walking down a staircase and been shaken from heel to head. From the outside, it looked like any other house in that part of Shinjuku, its face anonymous and secretive, its real life turned away from the street and passersby. The heavy wood doors could have withstood a battering ram but opened smoothly when he rang. In the anteroom, instead of Junyo or Aoyagi to greet him a muscular young man in the uniform of Junyo’s Samurai society was bowing stiffly, his white uniform with high collar, epaulets and tiny brass buttons in the shape of the sun goddess almost operatic or musical comedy. Not at all what Junyo intended, Jeffrey Middleton was sure, suppressing his smile. The young man’s stern face and military bearing did not relax when Middleton thanked him in Japanese and gave his name. The flickering eyes remained alert, suspicious, and for a moment, Middleton was certain the man would want to search him. Then the Samurai bowed and waved him past, saying in stilted English that Ohki-san awaited him in the office upstairs. Inside, the house reflected Junyo’s divided spirit, the more public part Western and filled with Queen Anne and Georgian antiques, richly ornamented and upholstered Chippendale and Hepplewhite pieces set on thick Oriental rugs, which contrasted with modern marble-topped Italian tables. The white walls bore old-fashioned silk-shaded sconces and gilt-framed paintings of barks, brigantines and frigates in full sail. The Japanese part of the house, into which, in the past, Middleton had been invited less frequently, was altogether uncluttered, wooden walls and tatami floors, moving screens, walls and windows. The office might have been a successful writer’s workroom anywhere but had the same East-West duality. On the shelves, windowsills, the two large refectory tables, everywhere, there were books, magazines, newspapers, piled helter-skelter around an electric typewriter here, a tape recorder there, reams of typing and carbon papers, Japanese writing brushes and bal1-point pens, four-plug telephones. But the enormous plank mahogany desk was coap1etely bare and behind it, under a modern glass light fixture shaped like a Japanese lantern, Junyo Ohki sat, elbows braced on the desk, his face in his hands. The only decoration in the functional room was a framed scroll on the wall above Ohki’s head on which were inscribed the five ideograms of “the way”: giri — duty; chugi — loyalty; chi — wisdom; jiu — benevolence; yu — valor, the code of the samurai. Middleton rapped softly on the open door, and Junyo’s face emerged from his hands. He rose, the expression on his features unchanged, moving from behind the desk as though he expected someone to stop him. He wore a T-shirt that revealed the muscular torso he had worked so long and hard to develop, his khaki pants sharply pressed, his feet in Japanese socks and sandals. And he stood tall. Junyo had long ago told him that once he thought white men a race of giants until he learned to know them; but Junyo remained self-conscious about his height, uneasy about Japanese being shorter than Americans, and it had always been one of the unexpressed tensions between Junyo and Ed Nicholas that Nick stood six feet three inches in his stocking feet and Junyo almost a foot shorter. Junyo bowed and Middleton bowed back, slightly lower as became his place, but Junyo’s words thrust him back on his heels as if he had been shoved. “Why did I have to learn from old Kuruhara of Miko’s death and not from you? More than a year has passed and still you have written me nothing of your grief, though I have a dozen letters about literary trifles. Is that the Western idea of friendship?” His eyes were slits, his Japanese hoarse and brusque. “I know that you were working to finish your book,” Middleton stammered in English. “1 didn’t want to disturb you.” “Disturb.” Junyo switched to English. “Is that the word?” He stalked to the large windows that took half of one wall of study. “Aren’t you going to ask me to sit?” “Sit if you wish.” Deliberately, although he was wearing Western shoes and trousers, Middleton sat, kneeling Japanese style on his haunches on a floor without tatami, his head bent, his eyes pressed shut. “I have been like a stone, falling, unable to utter a word,” he murmured in Japanese. “Even stones speak.” “Though my leg is missing, I still feel it. It cries out, it pains me, it wishes to be caressed.” Junyo turned from the window. “Old Kuruhara wrote that Miko’s was truly a seppuku. Why?” “Perhaps because her womb was barren, because she could neither conceive nor bear.” “Did she not speak of it to you?” “She was a daughter of Nippon. To have spoken of it would have been demeaning.” “Was there no way?” “The physicians told me that the fault was hers, yet there might be a way, but she would not listen.” Junyo averted his eyes. “We too have had such troubles, as you know, but Aoyagi is also a daughter of samurai yet she has not slit her throat.” “Miko’s was not a true seppuku,” Middleton forced himself to explain. “She slit her wrists.” Junyo’s biceps twitched, his fists clenched. “Was it because she was Japanese?” he asked in English. Middleton knew that Junyo was thinking of anti-Japanese sentiments in the States, so he shook his head, although, in another sense, it was precisely because Miko was Japanese. “Only in the sense that we never truly understood one another. However much we tried, even when we were most happy, our spirits remained strangers.” “All spirits are strangers to one another, like all people.” Abruptly, Junyo lifted him to his feet and led him to a chair. “Perhaps,” he ventured, “it was ensé?” Ensé, that mysterious Japanese weariness with life. Was that what had afflicted Miko? He remembered how, after his grandfather died, San-me ku’s eyes went lusterless, her features slack, her sprightly walk turned to a shuffle. Was that ensé? When Junyo spoke again, it was in an altogether different voice. “You should have written me, spoken your heart, as to a friend. Instead, you sent those niggling letters about con- tracts, about foreign rights, about how to translate this Japanese expression or that.” Middleton sailed. “One must live, and to live like this,” his waving arm took in the entire house, “one must be able to pay.” “Today there is a price tag for everything,” Junyo ranted. “Everything is business, overhead, sales, profits.” “What profiteth a man if —“ “ — he loses his own soul. That’s just what we Japanese have done under your able American know-how.” “Mitsui, Sumitomo and Mitsubishi needed lessons from no one.” “Once even zaibatsu knew their place, accepted that there were more important matters than coal and steel, sales and profits.” “The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere again?” “Even that had its grandeur.” “A lot of us disagreed with enough to fight a war against it,” Middleton said. “Then make war! More manly and honorable than jostling for markets to sell transistor radios and tweed cloth, this pushing like a bunch of clerks — ” he pronounced that word British-style “ — trying to elbow one another into the Underground.” He began to pace. “The nation I knew is disappearing before my eyes. Sons of Amaterasu, warriors filled with the spirit of bushi, are now a nation of merchants and shopkeepers.” That other nation of shopkeepers, Middleton reflected, that other great island nation, along them some of his ancestors, had fought that same battle to resolve it in a different way — and perhaps they too had lost. Whirling, Junyo dragged a second chair to the desk, sat and cocked his arm on the bare desktop. Middleton stood, slowly removed his jacket and draped it over the back of the chair. He rolled up the sleeve that bared his right arm and leaned his elbow on the desk. When Junyo’s sweating fingers fastened on his, they pressed the assault immediately; hands clasped, forearms locked, they strove against one another, arms swaying an inch this way, an inch that. “Remember when you taught me this?” Junyo gasped. Middleton nodded. The beginning. Junyo was only a scrawny student, really still a boy then. Surprised by his avidity to learn all things American and stunned by his fierce competitiveness, Middleton had taught him to arm wrestle. From the very first, Junyo had struggled to win and each time they had met since, Junyo had challenged him to a contest but never been able to triumph. Times had changed though, by a great deal. Since those first encounters, mentor had become student, student mentor. Junyo Ohki was now a world-famous novelist, playwright and scenarist, while he remained an obscure translator and professor of Japanese and Chinese, proud of what Junyo had accomplished as only a teacher can be proud of a magnificently gifted student who far outstrips him. The contest was not fair because he was so much taller and heavier than Junyo, and although Junyo was younger and in superb physical trim, weightlifting and swimming had kept Middleton fit. He would have liked to preserve at least that modest superiority in arm wrestling which over the years he had demonstrated, yet something told him that the necessary occasion had arrived to allow Junyo to win. They sat straining against one another, the sweat beaded on Junyo’s forehead, running into his eyes, the muscles in his neck corded, and Middleton, arm quivering, at last let his arm be forced flat. With a cry of triumph that echoed in the room, Junyo leaped up and did a little dance to the window. A spearhead of sweat tapered to a point at his spine, darkening his shirt. “I never thought I would win,” he exulted, “Never, never!” “You always win, Junyo.” “The martial spirit — bushi!” Junyo rejoiced. A buzzer sounded and Junyo picked up one of the phones, said he would be down in ten minutes, to have the car ready. “We’re going to Haneda,” he explained when he hung up, “to greet the returning Corporal Muta.” “That soldier they found on Saipan?” “Imagine, Jeffrey, living in the wilderness since 1944, refusing to surrender even when he knew the war was over! That is true Japanese spirit!” Middleton remembered throwing satchel charges into the mouths of Saipan caves to seal them off because the Japanese wouldn’t com. out of them to surrender, though he pleaded with them through a bullhorn in their own language. Months later, when the caves were opened by others who went to search for souvenirs, he saw not only dead soldiers, but women and children, their bodies decomposed, their hair still black and richly growing. And American soldiers and Marines knocking the corpses’ teeth out for the gold. “Muta,” he said, “sounds like an idiot.” “You’ll never understand, will you?” Junyo said, stripping off his shirt and wiping his chest dry with it. He motioned Middleton to follow him into the bedroom where he flung off the rest of his clothes in a heap at his feet. Self-consciously displaying himself, he stood proud and naked, toweling himself vigorously. It was a body of which Junyo could well be proud; on the verge of middle age, it was all muscle, defined pectorals and deltoids, biceps and triceps, without fat or flaccidity, a body Junyo had created for himself. The scrawny boy he’d been and the man he was now were like the before and after advertisements of Charles Atlas which had transfixed Middleton in the pulp magazines of his youth. One of the white Samurai uniforms was laid out on the enormous four-poster bed, a truly Victorian bed with side curtains, as far from Japanese tatami and futon as one could get. Junyo splashed himself with cologne, then, in minutes, he was dressed, grim and military. Outside, a uniformed young man was waiting at the wheel of a tan Toyota which he gunned down the street as if he were taking off from a carrier deck. “Twenty-six years,” Junyo said, “a lifetime. Kimmochi Muta was a youth when your troops took Saipan and drove him into hiding. Now he’s a middle-aged man.” “He simply gave up his life for nothing.” “Can Japan have lost if only one soldier of the Imperial Japanese Army preferred death to surrender, for twenty-six years lived alone and hunted, hiding in caves, eating rats?” “Muta did finally surrender.” “No! Two American sailors surprised him while he was trapping fish.” “You’re splitting hairs.” Junyo looked despairing. “Did you read what Muta said to the reporters? The Asahi printed his exact words: I would only like to tell the Emperor that I continued to live for His sake and believing in Him and Yamato-damashii.” Yamato-damashii, the traditional martial spirit of Nippon. Like Junyo and the arm wrestling, they never gave up. The American newspapers had also reported that Kimmochi Muta had confessed that he was afraid to surrender for fear that he might be damned as a traitor by his own people. “Now,” Junyo said “Muta’s coming home to Nippon, like a true soldier of the Emperor. Millions will be watching on television, and they will share his Yamato-damashii, those who once were part of it and those who do not even remember how it was.” “Is that why we’re going to Haneda?” “To greet the returning warrior and to remind all the sons of Amaterasu that there are still some of us who revere the Emperor.” At the airport the sky was overcast with low clouds that made the air a burden to breathe. The plane had set down half an hour earlier and already more than five thousand people were gathered. Middleton stood a distance back from the phalanx of three dozen white-uniformed Samurai who, with Junyo at their head, waited for Corporal Muta to alight. The JAL jetliner had been pulled right up on to the concrete apron, the staircase rolled into position. When the plane door opened, there was silence, then a spattering of applause like light rain, but no sooner had a beat, emaciated Japanese carrying a World War II rifle emerged when the acclaim grew into a stormy roar of “Muta! Muta!” The crowd surged forward, trying to break through the police cordon, which bent but held. Reporters and officials surrounded Muta as he walked haltingly toward the airport building. TV cameras atop several trucks and on the shoulders of photographers followed, then a microphone was held in front of Muta’s mouth. As if someone had given orders, there was sudden silence. Muta stood still, his eyes taking in the crowd, then he drew himself erect and with one hand held the rifle high over his head. Thin reedy words floated over them like cherry blossoms. “I have come home to Nippon with the rifle the Emperor gave me. I regret that I did not serve him better than I did.” The silence lasted until Junyo and his cohorts began to chant in unison, “Aikokushin! Aikokushin!” and held up placards inscribed with the three ideographs that meant heart, love and country; together they made up the word the Samurai were chanting which once had been a leading prewar Imperial slogan. A doctor and nurse appeared and Muta was seated in the wheelchair they brought. Rifle across his knees, his arms held high in greeting, Muta was wheeled through the crowd which parted to let him pass. As he disappeared through the doors of the airport lounge, a wave of screaming black-uniformed students came charging down on Junyo’s Samurai carrying signs that read, “We Are Unalterably Opposed to the Imperial Way!” Rocks and bottles flew, lead pipes were brandished, blows struck. A Samurai was beaten to the ground by two stave-wielding students. Junyo was at the very center of the fighting, his face alight with joy of combat, his teeth bared, using both his arms and legs. His Samurai were outnumbered ten to one yet Middleton felt no urge to join them in the defense of the Imperial Way, or for that matter Corporal Muta’s quarter century of pointless sacrifice. What, he wondered, possessed a Muta? Was it really Yamato-damashii or psychopathology, the fear of shame and being shamed in a rigid culture. And were the two mutually exclusive? A siren wailed, a bullhorn roared, and the riot police with their shields and helmets charged in to separate the black and white uniforms. Junyo was laying about him energetically, fighting three students when Middleton saw the fourth with a pole sharpened to a spear point running at him from behind. “Junyo!” Middleton shouted, but Junyo couldn’t hear him. Middleton ran to intercept the spear but he knew he would be too late, then, just as the spear was thrust, Junyo shifted his ground, and the spear sliced along his side leaving a bright scarlet smear on the white uniform. Junyo went down on one knee, turned to see the student bearing down on him a second time. Clumsily, Junyo tried to evade him and, as the student tensed for the thrust, Middleton knocked him to the ground. He tore the pole from his fingers and as the student, eyes wide with fear, mouth agape, strove to get to his feet, Middleton slammed him back to the ground. Another black uniform plunged out of the melee, pipe raised to strike, and Middleton caught him with the pole, left across the shoulder, which sent the pipe clanging on the concrete, right across the chest to send the youth sprawling. Swinging the pole like a kendo stick, Middleton cleared a space around them until Junyo, clutching his side, blood seeping through his fingers, stood up next to him, then Middleton cut a path in front of them until they were clear of the fighting. Behind them the police were clubbing the combatants apart while two trucks with water cannon maneuvered into position. Some of the students and Samurai had already taken to their heels, pursued by the helmeted Kidotai and their riot sticks. Others were hammer-locked and run into paddy wagons. A little apart from the rest, standing next to one of the paddy wagons, a short, flat-faced man with a powerful peasant physique was directing the police efforts. At the Toyota, Junyo’s right side was dripping blood. He asked Middleton to get the car keys in his trouser pocket. Middleton found them, and embarrassed, realized that Junyo had an erection and had wanted to announce the fact to him. He helped Junyo into the back seat of the car, advised him to lie down, but Junyo refused. As Middleton was about to get into the driver’s seat, the youthful Samurai who had driven them there returned, one eye already blue and closing, his uniform torn and filthy. Only then did Junyo introduce them. “Hushino, Fumio,” he said brusquely. Fumio bowed hastily and looked nervously back to where the riot police were bombarding Samurai and students alike with torrents of white water. Fumio slipped into the driver’s seat and with his own keys started the car. “We must hurry,” he said, looking at Junyo’s bleeding, then back at the Kidotai water cannon. “It was Fukutake,” he said to Junyo, and Junyo nodded acknowledgment. When they were on the road, Middleton ripped Junyo’s jacket up the back, then tore the right side off to expose the wood still brimming with blood. “You’re lucky,” he said, “the boy gouged out some flesh but nothing to worry about.” Junyo glared. “I do not worry. This is not the way I am fated to die.” “I wish you’d told me that,” Middleton said in English, “so I wouldn’t have bothered to get into the fight.” He ripped the skivvy shirt into three strips and laid them along the gash to staunch the blood. With his bloodstained hand, Junyo held it in place. Fumio parked the car in the alley behind Junyo’s house and threw his soiled Samurai jacket over Junyo’s shoulders, glancing furtively up and down the alley to see if anyone noticed their going into the garden entrance. Inside the fence they walked on the stone path through the bonsai pine, Mongolian oak and cherry, passed a full-grown clump of shuddering bamboo, then a pond of golden carp swimming lazily around three jagged rocks which jutted up from the clear waters. A kasuga lantern a few feet away stood guard over them like a lighthouse over a shoal. On the platform, they took their shoes off, Fumio kneeling to remove Junyo’s for him, then went into the eighteen-mat room of the house. Junyo sent Fumio for a first-aid kit, then lay back on the tatami. In a few moments, looking like a scarecrow in the tattered remnants of his uniform, Junyo rose to his knees. Pressing the bloodied shirt to his side, he inclined his head and said gravely. “Once more you have saved my life, Jeffrey. You performed like a true warrior, good soldier.” You must have been a very good soldier.” Middleton sank down on the tatami and stared out at the garden, the waves of green flowing into the house like surf, the square-eyed kasuga lantern warning him — but of what? A good soldier? Had he really been a good soldier? He doubted it. He lacked the blind hatred and the blind patriotism, the urge to violence and vengeance. Then he noticed the tokonoma. In it, highlighted, was a scroll with a single ideograph, chikara, the Japanese word for power drawn from the shape of a sword. Beneath the scroll lay an old, magnificent seppuku dagger. “Once again, Jeffrey,” Junyo said in a weak voice, “you save my life and shape it for new opportunity, just as you have shaped my art.” A compliment Junyo meant but at the same time mocked. From the beginning, Junyo had set out to make him feel responsible for the “new Junyo Ohki,” wanting him to serve as father and mentor. At first, Middleton thought of the boy he befriended almost like a son or younger brother, but that soon passed. What had, in time, truly bound them together in steady, abiding affection, was their long, intimate collaboration as writer and translator. And this, despite the fact that Middleton had just as consistently admired Junyo’s work as he had disapproved of Junyo’s ideas and life, as though — as Junyo never tired of reminding him — the two could be separated. Junyo insisted that Middleton must feel responsible for his whole life, because if Junyo was “Middleton’s creation,” then wasn’t the “creator” responsible for his creation? But at bottom Middleton understood that to be a subterfuge and evasion, for Junyo no more considered himself anyone’s creation than Middleton did: If anyone in the world thought of himself as “self-created,” surely it was Junyo Ohki. Fumio returned with a full-fledged combat first-aid kit, and Middleton used it to cut the remains of the uniform away, swabbed the gash with surgical cotton, but except for a quiver of facial muscle, Junyo remained impassive. Middleton laid the sulfa-impregnated bandages across the wound and taped the ends into place. “Looks clean, but you ought to have a doctor examine it. Might need stitches.” Junyo nodded absentmindedly and Middleton doubted that he would see a physician. Cleaned up except for the discolored eye, wearing only a loin cloth, Fumio returned with hot saké and three beautiful red lacquer cups on a black lacquered tray. “You were sure it was Fukutake?” Junyo asked” and Fumio nodded, then poured the saké. Junyo raised his cup to the tokonoma, grating, “Chikara!” Fumio echoed the toast, but Middleton refused to drink to power or toast that niche. Silently, he waited until they were finished, then drank his saké. When Fumio refilled their cups, Middleton declined. He had to go. Junyo acquiesced, and Middleton thought Junyo might be in shock until he saw Fumio’s loincloth. Then he understood, set his cup down and left the room. On the platform, he put his shoes on and walked across the flat stones to the gate. Just before going through it, he looked back and saw the sliding windows of the eighteen-mat room shut and the blinds drawn.

|